By continuing to use our site, you consent to the processing of cookies, user data (location information, type and version of the OS, the type and version of the browser, the type of device and the resolution of its screen, the source of where the user came from, from which site or for what advertisement, language OS and Browser, which pages are opened and to which buttons the user presses, ip-address) for the purpose of site functioning, retargeting and statistical surveys and reviews. If you do not want your data to be processed, please leave the site.

The Voice of People With Breast Cancer

My treatment plan

This section will outline the general treatment plan for the following personalization options:

Stage IV

Type: IDC, ILC, Rare, I don’t know

Triple negativeExplore Each Step:

1. Referral to cancer program

2. Your first appointment with your oncologist

3. Choosing a treatment plan

4. Supportive and additional treatments

5. Monitoring treatment progress and disease progression

6. Palliative care and symptom management

7. Choosing to end treatment and transitioning to end-of-life careIntroduction

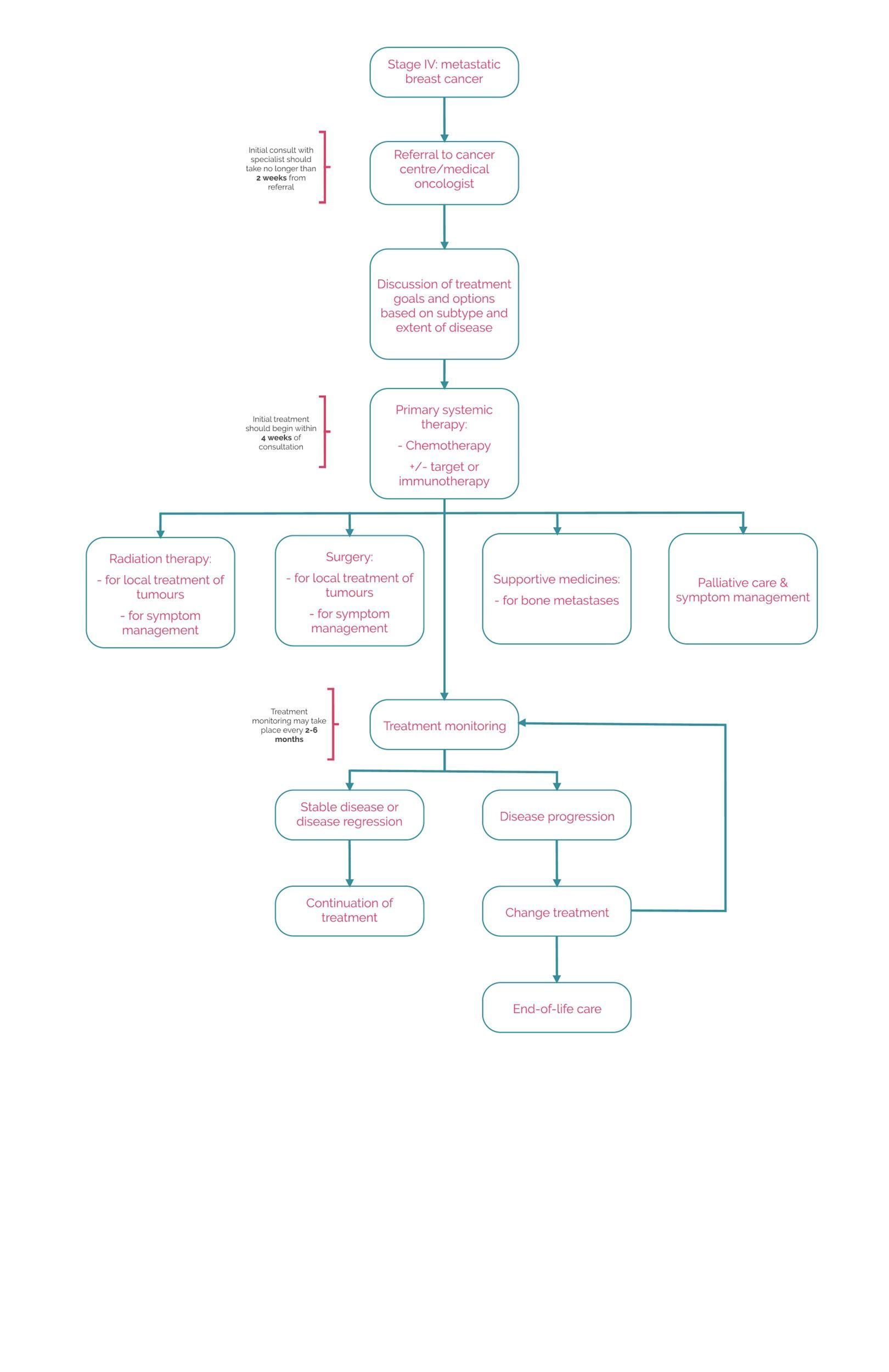

Oncologists follow specific guidelines when deciding on the treatment plan that is right for you. Below we outline the general guidelines and plans based on your stage, type and subtype of breast cancer. We also identify where you can make decisions about your treatment and what those options may be. Finally, we outline the pan-Canadian standards of care for access and timing of treatments.

Making decisions related to your care can feel like a heavy burden. These are decisions that can have a great impact on your quality of life in the immediate and sometimes distant future. Your first impulse may be to start treatment immediately. It’s important to understand that you have the time to get accurate information about your options, find useful resources (like this tool), get support, ask questions, and gain some perspective before having to decide on a course of treatment.

*Remember: Not all experiences may follow this exact path and you may or may not have all the tests or treatments we outline within. We hope this pathway will give you a general understanding of the process and possible timelines. The standards of care reported in this tool are based on guidelines and not everyone will fall into these standard categories. We encourage you to always consult your doctor for the most accurate information and timelines specific to your circumstances.

1. Referral to cancer program

After your diagnosis, your doctor will refer you to the closest cancer program.

Stage IV metastatic breast cancer means the cancer has spread beyond the breast to other parts of the body. Cancer cells that have spread are still considered breast cancer and will be treated with breast cancer treatment. Although it cannot be cured, treatment can help control the cancer and manage symptoms.

One of your first appointments will be with a medical oncologist. Your medical oncologist will be responsible for your primary care relating to your cancer treatment. They will work with you to make decisions about the types of treatments you will receive and can help you manage any symptoms of your cancer or side effects from your treatments.

In many provinces, triple-negative breast cancer is eligible for BRCA genetic testing. See our section on genetic and genomic testing to see if you are eligible based on your province and ask your oncologist about referring you for testing.

Tip: Ask about speaking to a social worker or patient navigator at your cancer centre. Oftentimes, these individuals can help you access practical and emotional support available at your centre or in your community to help you through your diagnosis.

Standards of Care:

- Many cancer programs in Canada aim for the first appointment with a medical oncologist to be within 2 to 4 weeks of referral[1] [2]. Actual timing varies by province.

2. Your first appointment with your oncologist

Treatment for stage IV metastatic breast cancer takes a different approach than earlier stages of the disease. The goal of treating metastatic breast cancer is to control the cancer growth, manage symptoms and maintain quality of life.

At your first appointment with your oncologist, they will review the treatment options available to you and help to answer any questions you may have about your diagnosis.

Your primary treatment will be systemic therapy (drug treatment), with radiation and surgery becoming additional treatments to help with symptom management. Your oncologist will go over what treatments they recommend for your subtype of cancer.

Some people are diagnosed with a type of metastatic breast cancer called oligometastatic disease. This is breast cancer that has spread to only a few spots (often under 5). Limited research on the definition and standards of care for oligometastatic disease means that treatment decisions vary by doctor and the person’s individual circumstances, like how aggressive the cancer is or where the cancer has spread. In some cases, surgery and radiation may be used and can be discussed at a Multidisciplinary Cancer Conference (MCC). MCCs are meetings where oncologists, surgeons, and other specialists review cases together to decide on the best treatment plan.

3. Choosing a treatment plan

When choosing a drug treatment, your oncologist will outline the recommended options for your breast cancer based on:

- Your previous treatment history (if you had breast cancer in the past)

- The location of the breast cancer metastases (lungs, liver, brain, bones, etc.)

- The results o your biopsy, including hormone receptor (HR) status, HER2 status, and other biomarkers (PD-L1 and BRCA status)

- Your overall health, which may influence what treatments are safe for you

- Your own preferences, goals and priorities

The very first treatment you receive is called first-line; the second treatment is called second-line and so on. When the first-line of therapy stops working you may move on to the next line of therapy.

Tip: Ask your oncologist about available clinical trials before beginning treatment. There may be some new treatments being studied in the first-line setting that you would not have access to if you have taken other metastatic breast cancer treatments. Read more about clinical trials here.

Below is an outline of the different treatments that may be offered to you with information on the line setting indications (whether they are approved for first-line, second-line, etc.).

Some drugs listed below are being developed and approved for use by Health Canada but may not be funded through all provincial or territorial drug formularies. This means it could require you to seek funding elsewhere (private insurance or manufacturer patient support programs) or pay a high out-of-pocket cost. Use our MedSearch drug database to see what drugs may treat your breast cancer.

Tip: Speak with your oncologist about how to access funding for these drugs and if there are any programs or drug access navigators at your cancer centre who can assist with paying for this drug.

Standards of Care:

- Treatment usually begins shortly after your consultation, once any required rests are done and the funding has been approved. Average wait times may be 2 to 4 weeks, but actual timing depends on the province.[3]

Immunotherapy

Immunotherapy helps the immune system detect and attack cancer cells. It blocks a protein called PD-L1, which allows cancer cells to hide from immune cells.

The primary immune checkpoint inhibitor developed for treatment of triple negative metastatic breast cancer is:

Pembrolizumab (Keytruda™) is an IV drug taken as a first-line treatment in combination with chemotherapy for people with PD-L1 positive triple negative metastatic breast cancer.

Chemotherapy

If PD-L1 is negative or immunotherapy is not an option, chemotherapy is the primary systemic therapy used for metastatic TNBC. Unlike early breast cancer treatments where strong combinations of chemotherapy drugs are given, treatment for metastatic breast cancer gives one drug at a time. This helps reduce potential side effects from treatment.

Some common single agent chemotherapies offered include[4]:

- Capecitabine: Given orally by pill

- Carboplatin: Given intravenously

- Doxorubicin: Given intravenously

- Eribulin: Given intravenously

- Gemcitabine: Given intravenously

- Pegylated liposomal doxorubicin: Given intravenously

- Paclitaxel: Given intravenously

- Paclitaxel-nab: Given intravenously

- Vinorelbine: Given intravenously

Combination chemotherapy may be considered on a case-by-case basis and is usually used when the cancer is progressing rapidly or causing serious symptoms.

Targeted Therapies

Antibody-Drug Conjugates (ADCs): ADCs are a type of therapy that links a targeted therapy with a chemotherapy drug. The targeted therapy helps deliver the chemotherapy directly into the cancer cell and are given intravenously.

Sacituzumab govitecan (SG, Trodelvy™) is an IV drug taken as a second- or third-line treatment.

BRCA targeted therapy: If you have an inherited BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutation, you may be eligible to receive a targeted therapy called olaparib.

Olaparib (Lynparza™) is an oral drug given to people with metastatic TNBC who have previously been treated with chemotherapy.

At any point in your treatment for metastatic breast cancer, you can ask about available clinical trials. Clinical trials may offer new treatment options along with additional monitoring. Some clinical trials require no initial first-line treatments to qualify, and some are available only to individuals who have progressed on standard treatments. Asking early in your diagnosis and when treatments are changed can help ensure you have exhausted all your clinical trial options. Read more about clinical trials here.

4. Supportive and additional treatments

Supportive treatments are added to help manage symptoms and protect affected areas of the body. They can be given along with your main treatments or as part of palliative care.

Local therapies are treatments that are given directly to the area where the cancer is located. Radiation and surgery are the two most common forms of local therapy for treating metastatic breast cancer. In some cases, local treatment can be used to help reduce the cancer. In most cases, it is used to help treat the side effects of the cancer. These treatments can be used to:

- Treat brain metastases

- Prevent bone fractures from bone metastases

- Treat cancer that is affecting the spinal cord or blood vessels

- Treat a small number of metastases (oligometastatic breast cancer)

- Provide pain or other symptom relief

The brain is a site where breast cancer is known to spread. These are called brain metastases. The three local forms of treatment for brain metastases include:

- Surgery can be performed if there are 1 or 2 lesions that can be safely removed

- Stereotactic radiation therapy can be used if there are a few lesions in the brain. For more information on this form of radiation click here.

- Whole brain radiation delivers radiation to the entire brain when there are many lesions.

The bones are another common site for breast cancer to metastasize. These are called bone metastases. In addition to radiation therapy and surgery, bone-strengthening medications may be used to help treat your bone metastases. These drugs include:

- Bisphosphonates that help strengthen the bone and stop the body from breaking down the bone. A common example is zoledronic acid given intravenously.

- Denosumab (Xgeva) is a bone-strengthening injection that helps reduce the risk of fractures and pain from metastases.

5. Monitoring treatment progress and disease progression

Your cancer and your treatments will be routinely monitored to ensure that the therapies prescribed are still working as anticipated. Your oncologist will also check for any side effects and adjust the dose if needed.

Systemic therapy is typically monitored every 2 or 3 cycles while overall disease monitoring can take place every 2-6 months.[5]Tests to monitor your treatment progress can include:

- Physical exams

- Complete blood count tests: this test looks at various characteristics of your blood including red or white blood cells, hemoglobin, or platelets

- Tumour marker tests: a blood test that is performed to look for substances produced by tumours. Some breast cancer, however, do not make these markers

- Bone scans: an imaging test that looks at bone abnormalities and can help monitor bone metastases

- CT scans: a 3D imaging machine that uses x-rays and computer technology to create detailed images of specific areas of the body

- X-ray: an imaging test that uses small amounts of radiation to create images of inside your body

Everyone reacts differently to treatment. For some people, certain treatments may work for long periods of time while other treatments may not work as well. If your cancer responds well to treatment your tests and scans may show:

- Stable disease: this means that the cancer has stopped growing/spreading

- Partial response/regression: this means that the cancer has decreased in size, but cancer is still visible on scans

- No evidence of disease (NED): this means no signs of cancer are seen on imaging or tests

Even if scans show no evidence of disease, microscopic cells can remain in the body, so ongoing treatment or monitoring is often needed.

If you respond well to treatment, your cancer can eventually grow to resist it, meaning that you will need to move on to another treatment. When your cancer continues to grow, or when new tumours appear, it is called progression.

If your follow-up tests show evidence of progression, you and your oncologist will discuss what other treatments may be available to you. This is also a good time to ask whether a clinical trial might be suitable for you.

6. Palliative care and symptom management

Palliative care and pain management are a large aspect of living with metastatic breast cancer. Palliative care focuses on relieving symptoms and supporting your physical, emotional and spiritual well-being. It can be incorporated into your treatment plan at any point where you feel you need it and can be used to improve your overall quality of life, not just at the end-of-life.

Palliative care can look different to each person and can be treated differently depending on your needs. It is coordinated through each provincial and territorial health system meaning it may look different depending on where you live. In some cases, your medical oncologist may take on the role of prescribing and managing your palliative care treatment. In others, your family doctor may coordinate palliative measures, or you may be referred to a palliative care specialist. Palliative teams may include nurses, counsellors or social workers who help you and your family manage symptoms and plan for future care.

Treatments for palliative care can include easing physical symptoms such as pain, nausea, vomiting and shortness of breath. They can also address the emotional aspects of a metastatic diagnosis such as fear, anxiety, or depression. A palliative care team may also help you access support for family or financial needs.

7. Choosing to end treatment and transitioning to end-of-life care

There will come a time when you, your family and/or your oncologist will decide to end your treatments and focus on your end-of-life care. This decision usually happens when treatments are no longer controlling the cancer. Making this decision can be difficult for you and your family.

Hospice palliative care will provide you with the same palliative options you have been receiving but with a focus on making you as comfortable as possible as you transition to end-of-life. It can take place in your home, a hospital, or a specialized hospice residence depending on your wishes and what’s available in your community.

Preparing for your end-of-life care in advance may help relieve some anxiety and fear. If you have specific wishes for your end-of-life care, creating an advanced care plan can help your loved ones understand your wishes and needs during your hospice care and after your death. It can also allow you to have a say in these decisions once you are no longer able to speak for yourself. For additional help, visit www.advancecareplanning.ca.

For more information about end-of-life care see End-of-life care section.

[1]Alberta Medical Association, Acute Care Concerns, Issue One: Cancer Care May 2024, page 1 https://www.albertadoctors.org/media/5blfpxm1/acute-care-concerns-cancer-care-issue-paper.pdf

[2]British Columbia Medical Journal, Deteriorating wait times for breast cancer patients at a regional hospital in BC, 2013 versus 2023, Table 4 https://bcmj.org/articles/deteriorating-wait-times-breast-cancer-patients-regional-hospital-bc-2013-versus-2023

[3]British Columbia Medical Journal, Deteriorating wait times for breast cancer patients at a regional hospital in BC, 2013 versus 2023, Table 4 https://bcmj.org/articles/deteriorating-wait-times-breast-cancer-patients-regional-hospital-bc-2013-versus-2023

[4] BC Cancer, Breast Cancer Chemotherapy Protocols: Advanced http://www.bccancer.bc.ca/health-professionals/clinical-resources/chemotherapy-protocols/breast#advanced

[5] Stewart D, MacDonald D, Awan A, et al. (2019) Optimal frequency of scans for patients on cancer therapies: A population kinetics assessment. Cancer Med 2019 Nov; 8(16): 6871-6886 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6853816/#