By Catalina Lopez-Correa

By Catalina Lopez-Correa

This post was originally published on Catalina’s LinkedIn.

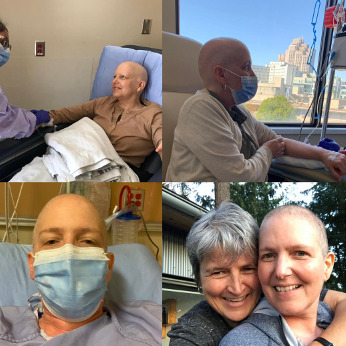

April 11th marked exactly one year since my breast cancer diagnosis. Needless to say, it's been a challenging journey, filled with physical, mental, and emotional hurdles.

Throughout this year, I've written several articles delving into various aspects and insights since my breast cancer diagnosis. I've discussed the diagnosis itself, my experiences with the healthcare system, and the pressing need for greater equity and access to healthcare innovation in general, and genomics in particular, not only for patients in Canada but around the globe.

Today, I want to dive into the role genomics has played in my journey. As an MD specialized in genomics, this journey has been an eye-opener regarding the clinical implementation of genomics and the accessibility of genomic profiling for real patients in British Columbia, Canada, and beyond. There have been good surprises and also situations where I've directly faced barriers and limitations surrounding the clinical use and implementation of genomics.

On the positive side, I was pleasantly surprised to learn that all breast cancer patients in Canada (and globally, as far as I know) receive three biomarkers—estrogen, progesterone, and HER2—to refine diagnosis and guide their treatment. This standard of care exemplifies the power of precision oncology, recognizing breast cancer as a diverse group of diseases with distinct treatments and prognoses based on these biomarkers.

Though I didn't request it, these tests are part of the basic diagnostic protocol for all breast cancer patients. However, as an MD and scientist with over 20 years of experience in genomics, I was eager to delve deeper into my tumor's genomic makeup. Naively hopeful about genomics' potential, my initial query to my surgeon was about sequencing the entire genome of my tumor. However, my incredible surgeon, in her wisdom, explained the protocols and processes involved, suggesting I consult my oncologist regarding genomic profiling options. Seeing my enthusiasm for science and research, my surgeon offered me participation in a gut microbiome study, which led to further genomic tests either being offered or requested.

Here's a summary of the genomic tests I've undergone so far:

1. The first "omic study" I participated in analyzed my gut microbiome. This collaboration between UBC and the BC Cancer Agency (Gut Microbiome and Breast Cancer) explores how gut bacteria may influence estrogen levels and breast cancer development. While this study doesn't directly impact my diagnosis or treatment, I've contributed to advancing scientific knowledge by providing stool, blood samples and filling a long questionnaire. Hopefully I will see the aggregated results of this study in a publication.

2. The second test involved genomic profiling of my tumor. Upon direct inquiry, my oncologist suggested I join a clinical study offering a genomic test of my tumor tissue. There are several versions of this test (OncotypeDx, Mammaprint, Prosigna, etc) that analyze a limited number of genes in the tumor. The one I got was the OncotypeDx, indicated for individuals diagnosed with early-stage invasive breast cancer that are estrogen receptor positive (ER+) and HER2 negative (HER2-). The results of this genomic test were crucial in determining the necessity for chemotherapy based on my tumor's characteristics and clinical history, and in defining the prognosis and risk of future recurrencies. More information about these tests and how to get access to them in Canada can be found at the Canadian Breast Cancer Network Genomic testing Advocacy Guide.

3. As a scientist, I was keen on exploring whether I carried any hereditary cancer genes. I asked my oncologist if I could get the hereditary cancer test. I call this the “Angelina Jolie test”, and for years I have used this example in my conferences and presentations about precision oncology, personalized medicine and genomics as a way to illustrate how hereditary cancer genes can lead to drastic and important medical actions (e.g. double mastectomy) to help prevent cancer. Unfortunately, in my case, since I have no close relatives with breast cancer, this test is not covered by the health care system. I decided to pay for the test myself (saliva sample that must be shipped to the US!) and receiving reassuring results indicating no mutations in tested genes.

4. Nearly a year post-diagnosis, changes in the selection criteria for the Personalized OncoGenomics program allowed me to participate in this initiative. I eagerly consented to whole-genome sequencing of my tumor and my constitutional DNA (blood), aiming to guide future treatments and enhance prognostic understanding.

These tests exemplify the strides made in precision oncology. General information about genetic and genomic testing can be found at this site of the Canadian Cancer Society. However, accessibility remains an issue. While genetic and genomic testing resources exist, equitable access remains elusive, particularly for patients in underserved regions or for patients from equity deserving groups.

A few reflections and lessons learned:

1. Patient advocacy is paramount. This journey underscores the importance of asserting one's voice, asking questions, and seeking second opinions. Persistence in advocating for beneficial treatments or tests is vital.

2. Accessibility to genomic tests remains a global challenge. Patients in the Global South, and even patients in certain regions of the US and Canada, find it challenging to access some of these tests. We must continue advocating for more health equity and increased access to health care innovation in Canada and around the world.

3. We have invested millions of dollars to advance the use of genomics in Canada. It is frustrating to see that for two of my genomic tests the samples had to go to the US for analysis. We should be able to develop that capacity in Canada, for the benefit of our patients.

4. Other test that could be relevant, and that I am trying to access are not yet available for patients in Canada, or at least not available for me. For example, I am interested in getting a test that indicate if I have tumoral DNA circulating in my blood (ctDNA). This test could help guide treatments and define if a patient is in full remission.

In conclusion, my journey highlights the necessity of self-advocacy and the ongoing pursuit of equitable access to cutting-edge healthcare advancements, particularly in genomics. The promise of precision medicine can only be fulfilled when patients directly benefit from these advancements. This journey has underscored the importance of speaking up and questioning, while also revealing the substantial work yet to be done in ensuring universal access to healthcare innovations, especially in genomics.

Dr. Catalina Lopez-Correa is Chief Scientific Officer with Genome Canada, and Executive Director of the Canadian COVID Genomics Network. With more than 20 years of experience in supporting and advancing genomic solutions to address local and global challenges, she believes in the power of collective efforts and interdisciplinary approaches to tackle complex challenges.